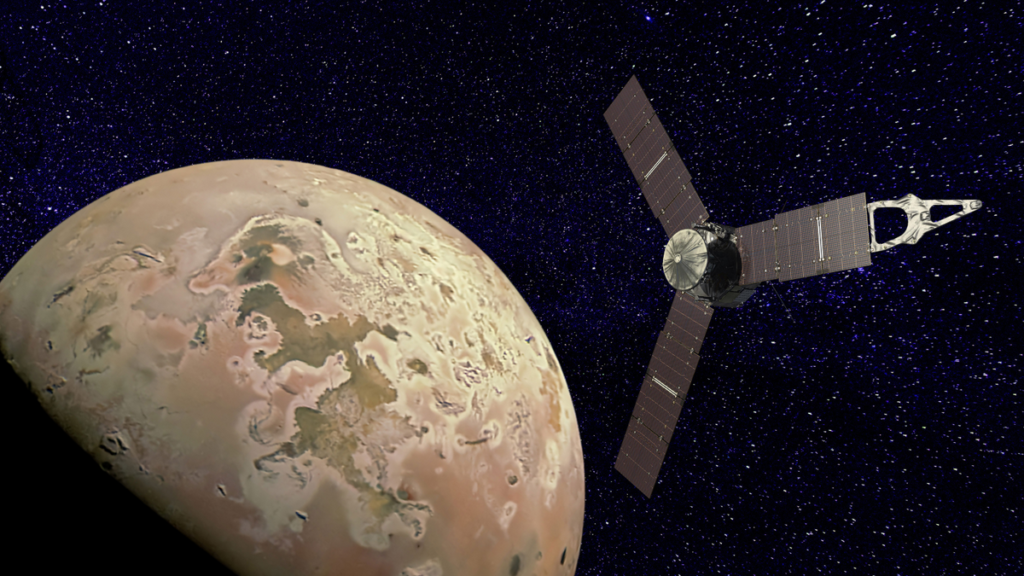

On Saturday, December 30, NASA’s Juno mission will get closer to Jupiter’s moon Io than any spacecraft has in about 20 years.

During the flyby, Juno will travel around 1,500 kilometers or 930 miles across Io, the solar system’s most volcanically active planet. This will enable the spacecraft to collect an abundance of valuable data while taking a close look at Io. Though it’s not the closest view ever captured by a spacecraft, NASA’s Galileo probe set a record in 2001 when it skimmed barely 181 kilometers (112 miles) above Io’s south pole.

Launched on August 5, 2011, Juno traveled 1.7 billion miles (2.8 billion kilometers) to arrive at the gas giant Jupiter, the biggest planet in the solar system, on July 4, 2016. The Jupiter orbiter began its next flyby of the gas planet shortly after that, having completed 56 flybyys since then, gathering data on the planet and its moons.

According to a statement from Southwest Research Institute scientist and Juno principal investigator Scott Bolton, “The science team is studying how Io’s volcanoes vary by combining data from this flyby with our previous observations.” We are searching for information on their frequency, brightness, and temperature as well as the way the lava flow changes shape and how Io’s activity is related to the movement of charged particles in Jupiter’s magnetosphere.

Having completed its primary mission in July 2021, Juno is currently in its third year of an extended mission. On February 3, 2024, the spacecraft will travel close to Io, coming within around 930 miles (1,500 km) of the volcanic surface of this Jovian world.

Thanks to Juno, which has been tracking Io’s volcanic activity from distances ranging from 6,830 miles (11,000 km) to over 62,100 miles (100,000 km), the flybys of Io in December 2023 and February 2024 will contribute to the wealth of knowledge that scientists have gained about Io. The NASA probe has also given scientists their first-ever looks at Io’s north and south poles while it has been in operation.

Why look at Io, the “tortured moon” of Jupiter?

There are hundreds of active volcanoes on the moon Io, which is about the size of Earth, that can shoot lava hundreds of miles into the thin, waterless atmosphere of the Jovian moon.

The gravitational pull of Jupiter and its three other Galilean moons, Europa, Ganymede, and Callisto, is thought to be the reason behind the intense volcanic activity of Io, the innermost of Jupiter’s four major moons.

Extreme volcanism can result from these tidal forces, which can cause Io’s surface to rise and fall by as much as 330 feet (100 meters).

According to Bolton, Juno will examine the origin of Io’s intense volcanic activity, if a magma ocean lies beneath its surface, and the significance of Jupiter’s tidal forces, which are continuously compressing this afflicted moon, during our two close flybys in December and February.

Understanding Io’s volcanism is important since it probably affects the larger Jovian system. For instance, it’s believed that volcanic particles that break free from Io’s atmosphere are caught by Jupiter’s magnetic field and produce a heated donut-shaped region of plasma surrounding the gas giant planet.

The NASA orbiter Juno will skirt the Jovian moon on each of its ensuing rounds of Jupiter after its orbit of Io in February 2024, although each orbit will get farther away from the volcanic surface of Io.

Following February, the NASA spacecraft will make two flybys of Io. The first will occur at an altitude of roughly 10,250 miles (16,500 km), while the last will bring the spacecraft to a proximity of approximately 71,450 miles (115,000 km) on the volcanic moon.

Additionally, Juno will now start to experience times when Jupiter passes in front of the sun, preventing it from receiving solar energy and causing it to experience darkness for the first time since leaving Earth.

This shouldn’t affect Juno’s operations; starting in April 2024, the spacecraft will use these occultation events to support its Gravity Science Experiment, which looks into the composition of Jupiter’s upper atmosphere and gathers data about the planet’s interior structure and shape.

NASA states that Juno’s extended mission to study the Jovian system will expire in September 2025, at which point the spacecraft will likely approach the end of its useful life and be purposefully crashed into the gas giant’s atmosphere.